How to Live Forever, with Ru Freeman

This is the fourth installment in a column highlighting Asian American writers/books. It is important that we start acknowledging that Asian American experiences are the stuff of literature, of music, of movies, of culture, and that we start supporting those efforts and spreading word of those efforts far and wide. I read hardly any Asian American writers when I was in elementary school, or middle school, or high school, and it was only in college that I found voices that spoke for the importance of minorities, that made me understand that my experiences were worth something.

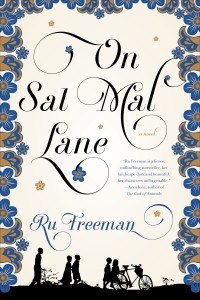

Ru Freeman is the author of On Sal Mal Lane and A Disobedient Girl, which was a finalist for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature and has been translated into seven languages. She is an activist and journalist whose work appears internationally. She calls both Sri Lanka and America home.

On the day the Herath family moves in, Sal Mal Lane is still a quiet street, disturbed only by the cries of the children whose triumphs and tragedies sustain the families that live there. As the neighbors adapt to the newcomers in different ways, the children fill their days with cricket matches, romantic crushes, and small rivalries. But the tremors of civil war are mounting, and the conflict threatens to engulf them all.

EARLY ON IN MY CONVERSATION with novelist Ru Freeman, in a bar in New York’s Greenwich Village, she says something that will stay with me as I finish her momentum-filled latest, On Sal Mal Lane. She says that in Sri Lanka, her birth country and the country in which the novel is set, children are coddled, but not from death.

In On Sal Mal Lane, one of the major storylines is the attempts of a brother to keep a sister safe from a fate many of their neighbors insist is coming: an early death, courtesy of an unlucky birthday: July 7th. The sister in danger is the youngest daughter in the Herath family: the baby, watched and worried over while she makes it hard on her sibling and parents by being somewhat of a troublemaker.

“So much is expected of girls,” Freeman says when I ask about her own childhood in Sri Lanka, during the war that is just beginning by the end of On Sal Mal Lane. Freeman migrated from Sri Lanka to America for college. At the time, universities in Sri Lanka were closed, she explains. Her brother was politically involved, and even ended up imprisoned. Her father, like Mr. Herath, worked in the government but not as a member of a specific party. The Freemans’ home, as the Heraths’ home becomes, was a type of sanctuary, not only for her family but for others.

Freeman explains that the mix of families on Sal Mal Lane (in religion, race, politics, economic level) is representative of the country. The interactions that play out in microcosm on the street also played out across the island. All the more important, then, that we understand these characters as well as Freeman helps us to understand them. She tells me she wanted to write with compassion, saying, as writers tend to do, that fiction does not have a political agenda, that fiction is not journalism—part of why she wanted to look at all different perspectives, and part of where the novel’s good old Tolstoyan omniscient narrator comes in.

“It is better to save our neighbors,” the eldest Herath son says at the start of the riots, “than to attack other people’s neighbors.” At points, that statement seems at the center of this book.

Freeman had to win a scholarship in order to escape the war. She was “supposed” to be a human rights lawyer. That was how she planned to make a life of her story, through work in social justice (which she still does). She says she has to get “worked up” to do something about a particular issue. I know this feeling in my own essays, and by the end of On Sal Mal Lane, you want to do something—not because you get worked up in anger, so much, but because Freeman hits all the right emotional notes, and you care about these people enough that you feel as if you care about the whole of Sri Lanka.

We are bolstered throughout by Freeman’s compassion (though we are never coddled from death and loss and tragedy). The residents of Sal Mal Lane take us through the spectrum of emotion.

Freeman has been asked why she doesn’t write more about the politics of Sri Lanka. She knows the politics. She gave the keynote recently at a Sri Lankan conference, where her brother, a scholar and someone Freeman looks up to personally and intellectually, was in attendance. She says he grilled her, and afterward, said, “Either you’re very smart or you’re a great bullshitter.”

It’s hard to write anything set in South Asia without writing about the political situations, Freeman tells me. But the characters, and the story–that all important bullshitting–are what mattered to her. “One good thing,” she writes in On Sal Mal Lane, “was enough to make a life remarkable.” (Though on the next page: “In those moments he would feel that he was neither full of war nor full of peace, he was simply lost.”)

When the Herath children must finally deal with death, they must deal with existence in the face of nonexistence, with creating an environment, as in writing, where a person who is not “alive” walks at one’s side. “Make something,” is the decree. It is good for us that Freeman gave up law to be a writer, since she has the rare gift of being able to make life out of death.

–author photo by Brenda Carpenter

Pingback: Weekend Fiction: Excerpt from On Sal Mal Lane, by Ru Freeman — The Good Men Project