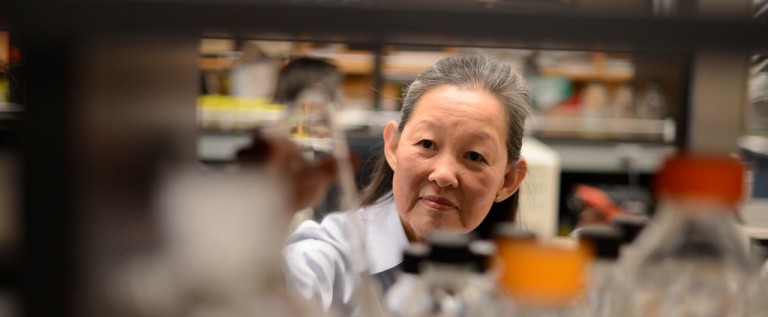

Alice Huang, Science Pioneer Extraordinaire

Alice Huang recalls the moment she knew that science would become her chosen field of study. In her college microbiology class, her eyes widened when she looked into the microscope and saw all the bacteria and cells that were otherwise “invisible.”

A few years later, Huang earned her PhD in Microbiology from the prestigious Johns Hopkins University, and started to build an illustrious career. She spent more than twenty years as a faculty member at Harvard Medical School, and later became the Dean for Science at the New York University. She also served on the Board of Trustees of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Johns Hopkins University, as well as the Rockefeller Foundation and the Waksman Foundation. More recently, she served as President of the American Association for the Advancement of Society from 2010 to 2011.

Photo by Eric Bothwell for ALIST Magazine

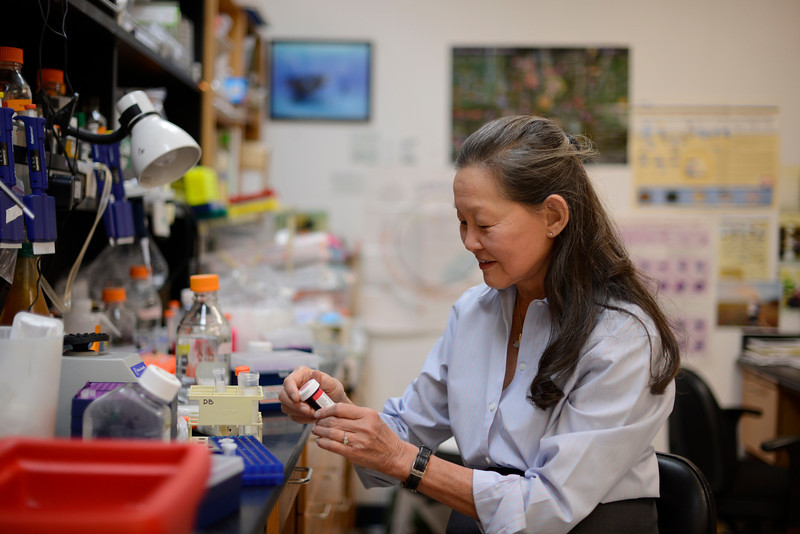

Today, Huang is a Senior Faculty Associate at the California Institute of Technology. Her research primarily centers on studies of microbiology and virology. She is best known for her graduate work with then-mentor Nobel laureate David Baltimore, who is now her husband. Huang’s research helped him discover the important biological process of reverse transcriptase, essential for the reproduction of retroviruses such as HIV. Huang is also an active proponent of women in the sciences and received the Alice C. Evans award in 2001 for her work helping and promoting the study of sciences for women.

A Troubling Pipeline for Science Research

When Huang was younger, shedid not know of any female scientists she could look to as role models. She ended up looking to John Enders, the 1953 Nobel Laureate, for inspiration. Enders was the first man to successfully grow the poliovirus in a cell line, thereby opening up the whole ability to work with the poliovirus. This eventually led to the development of the polio vaccine.

Although there are now more female scientists, Huang is worried about the future pipeline. Huang points out that despite the high number of qualified women in science research, studies have suggested that they are not promoted as frequently as their male counterparts. Huang emphasizes that there is still work to do to ensure that “access to education, information, and job options is equal for both sexes.”

Photo by Eric Bothwell for ALIST Magazine

Further, the general lack of enthusiasm for science and math for girls in the U.S. concerns Huang.Her worry is echoed by others. According to the Washington Post story, “Decoding Why Few Girls Like Math, Science,” girls more often choose to study the humanities or sciences, as opposed to more “advanced elective courses,” such as applied physics or mathematics.

Part of this problem stems from the way in which students are educated about math and science, and the attitudes they develop towards these subjects when they are young. Huang suggests that the solution lies in changing our approach to Math and Science education. Huang emphasizes the importance of making science and math more relatable to students, suggesting that professors should try to approach science and technology in more engaging and relevant ways.She says, “You can’t just stand up and write on the blackboard with your back to the students and then test them on what you’ve mumbled through lectures.”

Furthermore, Huang notes that the problem starts with the way kids are educated at a young age. “[The periods of] junior high and high school are the most important, but we have already turned off a lot of kids [by] grade school.In the end, they never want to study science and math because their introductions to science and math were not interesting.” Huang adds that university professors should also be trained to teach well to encourage enthusiasm for math and science in college student bodies.

Doing More

On the role of Asian Americans in American society, Huang has pointed observations. She notes that, “When we look at some of the more recent statistics for Asian Americans, we realize that we are not contributing as much as we can to this country.” She especially laments the lack of Asian American influence in the US political realm. Historically, international conflicts have always had serious consequences for minority groups in the US – especially those that do not have significant political influence. As China grows in importance on the world stage and begins to assert itself – perhaps in ways that the U.S. may not approve of – one cannot help but agree with Huang’s ominous observations.

“We have the capabilities, but … we don’t look at the bigger picture of how this country will be shaped and how it will treat Asian Americans in the future.”

This reminds us of a question that we hear from many Asian Americans – why stick our necks out and be a leader? The answer, as Huang alludes, is that if we do not actively participate in shaping the future of the US, our children could be written out of it. Huang points out that young people play a crucial role. She thinks it is important to help all Asian Americans participate fully in American society, whether in the political, business, or other realms.Huang says, “This is our adopted country and it’s important that we don’t [just] take the best things for ourselves and our families, but that we do give back in some ways to help future Asian American [generations].”