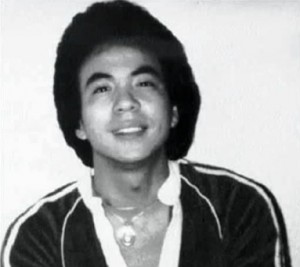

We are Vincent Chin

He was the API community’s Trayvon Martin, the API’s Rodney King: a terrible reminder of the failure of the justice system that galvanized the first substantial pan-Asian movement for solidarity, advancement and civil rights. “I want justice for my son,” said Lily Chin thirty years ago, and every day until her departure in 2002. Lily Chin’s wishes were echoed on June 23, 2012 when 30 cities across the country commemorated the 30th anniversary of her son’s tragic beating death in a series of coordinated town halls called “VC30: Standing Up Then and Now”. In 1982, while out for his bachelor party, Vincent Chin was attacked by Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz, laid-off Detroit autoworkers. “It’s because of you little m—f—s we’re out of work,” the assailants yelled while beating Chin. They mistakenly assumed Chin was Japanese. After the initial scuffle, Ebens and Nitz hunted for Chin and beat him with a baseball bat until his skull cracked.

They never spent a day in prison.

Neither Ebens nor Nitz denied the actions in court. However, without notifying the police officers at the scene or Chin’s lawyers, the prosecutors struck a plea bargain, which reduced the second-degree murder charges to manslaughter. The judge sentenced the perpetrators to a lenient three years of probation and $3,000 fine.

Later, under public pressure, charges were brought to federal court against Ebens and Nitz for killing Chin based on his race, thus violating his civil rights. After a civil rights trial in Detroit, an overturned conviction, and a botched re-trial in Cincinnati, the two men were cleared of all charges.

They never spent a day in prison.

“I could see in [Lily Chin’s] eyes that she had lost everything,’’ recalled Stewart Kwoh, one of the lawyers who advocated for a civil rights trial and the current Executive Director of the Asian Pacific American Legal Center. “What happened was not just a tragedy for her and her family, but an indictment of the U.S. justice system.”

Out of the ashes of that historic miscarriage of justice, thousands of activists marched and worked together across ethnic lines to create the first substantial Asian American movement. It was the Vincent Chin case that inspired many to start civic and advocacy organizations, including the National Association of Asian American Professionals (NAAAP). NAAAP was established in 1982 as many Asian American professionals identified with Vincent Chin’s story and were inspired by the civil rights activism.

From the Chinese Exclusion Act to Private Danny Chen

Chin, a 27 year-old engineer, could not escape the discrimination and scapegoating that many of his ancestors endured a century before. In 1882, exactly 100 years before Chin’s death, discrimination and vilification of Asians was institutionalized in the first and only race-based restriction law passed in the nation, banning entry of Chinese and denying citizenship rights to those already here.

It would take 130 years for Congress to pass a resolution apologizing for the Chinese Exclusion Act. The resolution was championed by Representative Judy Chu (CA-32), who was a panelist on the Jun 23 VC30 virtual town hall. “Vincent was a tragic victim of the perpetual foreigner stereotype and the rampant xenophobia,” Chu said.

The virtual panel and local discussion groups denounced the “orientalist” and fear-mongering political ads that framed Chinese as job-stealers in the 2012 elections.

The VC30 event also addressed the recent release of Asian Americans Rising report by the Pew Research Center. It reported that Asians replaced Latinos as the country’s fastest-growing ethnic group and that Asian-Americans in aggregate have higher incomes and better educations than whites, blacks or Latinos–they even the “happiest” group. “What’s worse, this report pits Asians against Latinos, implying Latinos lag behind and Asians have made it – and the resentment that can create,” Chu said. “When those realities are hidden beyond the model minority myth, the challenges remain unmet.”

Painting such a monolithic picture of the fastest growing demographic begs the question of how much the media and other public institutions have critical API professionals and perspectives. “We need to jump into the mainstream media,” urged Zahra Billoo, executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations in San Francisco. She challenged the audience to imagine whether a report like this would have been more accurate if there were Asian Americans throughout the process. “We also need to control our narrative, and create our own media and report; we need to put out our own ideas,” Billoo added.

Vincent Chin’s killing led to an unprecedented alliance-building within the API community. “Hate crimes affect not just one person, but an entire community,” Billoo said.

Others on the panel discussed how they are taking grassroots initiatives to address hate crimes and bullying in their own communities, from bullying of Asian students at a Philadelphia high school to ending military hazing that has led to the suicides of Asian American soldiers such as Private Danny Chen and Rep. Chu’s own nephew, Lance Corporal Harry Lew.

Vincent Chin’s Legacy

From professional advancement, to addressing the needs of those who are discriminated or disenfranchised in the Asian American community, to building political power across ethnic and racial lines, there is plenty of work ahead.

Vincent quickly assimilated in his adopted family and homeland, but that did not matter in the eyes of those who were resentful in the backdrop of economic hardship. A whole new generation has sprung up since 1982. As the API community continue to grow, diversify and unite, remembering Vincent Chin will always be the focal point for not just the Asian American experience but for the entire nation to learn and chart a more inclusive and just path ahead.

Pages: 1 2

Pingback: Perpetual Foreigners | languid curiosity