How to Write a Debut Novel, in 15 “steps”

This is the first installment of a new column highlighting Asian American writers. It is important that we start acknowledging that Asian American experiences are the stuff of literature, of music, of movies, of culture, and that we start supporting those efforts and spreading word of those efforts far and wide. I read hardly any Asian American writers when I was in elementary school, or middle school, or high school, and it was only in college that I found voices that spoke for the importance of minorities, that made me understand that my experiences were worth something.

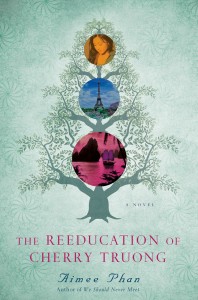

I am so pleased to start this series off with Aimee Phan, whose first novel, The Reeducation of Cherry Truong, is out in paperback this month. An excerpt to read along with this column can be found in The Good Men Project.

Aimee Phan grew up in Orange County, California, and now teaches in the MFA Writing Program and Writing and Literature Program at California College of the Arts. A 2010 National Endowment of the Arts Creative Writing Fellow, Aimee received her MFA from the University of Iowa, where she won a Maytag Fellowship.

Her first book, We Should Never Meet, was named a Notable Book by the Kiryama Prize in fiction and a finalist for the 2005 Asian American Literary Awards. She has received fellowships from the MacDowell Arts Colony and Hedgebrook. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, USA Today, Guernica, The Rumpus, and The Oregonian, among others.

In The Reeducation of Cherry Truong, Cherry Truong’s parents have exiled her wayward older brother from their Southern California home, sending him to Vietnam to live with distant relatives. Determined to bring him back, 21-year-old Cherry travels to their homeland and finds herself on a journey to uncover her family’s decades-old secrets—hidden loves, desperate choices, and lives ripped apart by the march of war and currents of history.

How to Write a Debut Novel, in 15 “steps”

by Matthew Salesses

1. First be generous, smart, kind, persistent. You have been working on your novel for 8 years. These have not been years of research. But you have written a novel someone might suspect took 8 years of research. You have written a novel full of heart, full of perception, full of insight. You have written a novel in many voices, and yet in one voice. You have written a novel called, The Reeducation of Cherry Truong.

You are Aimee Phan.

2. I too have been working on a novel for 8+ years. It becomes a part of one’s identity, to be someone who has worked on a single creative project for so long. I can understand wanting to give up and/or being too stubborn or loving to do so.

You didn’t give up on your novel. I understand what you mean when you say the characters in your book mean more than some friendships.

3. Sometimes it seems like there are two types of writers, and that these two types become most apparent when they hear about someone working on a book for a short time (a year) or a long time (8 years). There are those writers who believe a book should take a long time, and there are those writers who write quickly.

I believe a book should take a long time to write because I am afraid that I am doing it wrong.

The Reeducation of Cherry Truong is just right. It is a book of more than one kind of hope.

4. You say the book is your baby. You are a parent of two books and two children. Your first book was a story collection. Working on stories brought you to your novel. You were writing individual stories of characters that merged into one large, extended Vietnamese American family.

You say that is the way you view your family history: “Each family member has a treasure trove of secrets.” You say: “This novel would be a way to explore different family members and how their pasts affect their children’s lives.”

Your book is a book of merging.

5. If our books are our babies, how do we affect them? How do they affect us?

6. As a new father, I ask you about parenting. You are still trying to figure out your philosophy. You say parenting is more rewarding than writing. I do not wonder whether writers who write a book a year would say the same.

Having a child has helped you to understand your parents better. The same for writing The Reeducation of Cherry Truong. In that way, they are similar: books and children. They illuminate the past.

Your book is a book that would help any child better understand his parent, I think. That is one of the great things one can say about a book, I think.

7. When you say you can see yourself becoming your mother, I think there is a writing metaphor in there somewhere.

When you say you hope you are less stubborn than your mother, I am still thinking about books as babies.

Your book is an understanding book.

8. On the back cover of The Reeducation of Cherry Truong, another Asian American writer I admire, Alexander Chee, calls your book “a powerful debut novel about reverse migration, the new American immigrant story.” I am someone always realizing more and more that I have been stuck between countries. I have considered reverse migration. You write about a brother who moves to Vietnam, where he was born and from where he fled as a toddler. You thought this character would be the “oddball,” until you saw more and more Vietnamese Americans going to Vietnam.

your book “a powerful debut novel about reverse migration, the new American immigrant story.” I am someone always realizing more and more that I have been stuck between countries. I have considered reverse migration. You write about a brother who moves to Vietnam, where he was born and from where he fled as a toddler. You thought this character would be the “oddball,” until you saw more and more Vietnamese Americans going to Vietnam.

You have written about one family’s story, and you have written about many families’ stories.

9. You wrote a book full of secrets and secret-keeping. “Fiction,” you say, “is all about discovery and decision.”

10. In your book, each chapter starts with a mailed letter. Much of what is in these letters is, at least at first, secret from the reader. We try to put together the information, the relationships between the letter-writers and letter-receivers, the things that are secret and the things that are not. We live, for much of the book, in mystery.

This is a book a reader might call “a page-turner.”

11. It is one of the secrets of the book that the story carries the reader along so quickly and the wisdom sneaks up along the edges, or from below, as if the story is a boat on a wide ocean, and wisdom is a creature of the sea.

One of the secrets to how your book works is that we forget which secrets are being kept and which are not secrets any longer. We forget information we know. Things live between mystery and knowledge.

12. The first sentences of your novel: “Mother, I hope this finds you well. I think about you and our family often. I think about you every hour of every day.”

13. You wrote your own family history into the family history in this book. You used your family’s departure from Vietnam. You used your family tree, though with fewer aunts and uncles.

You grew up not far from Little Saigon.

Your mother sounds similar to the mother in your book, powerful and sometimes scary.

You wrote about memory loss while your father was developing Alzheimer’s.

14. You say these stories are important for your kids, “more than any other reader.” You say, “That means more to me now than I ever thought it did.”

Children, and books. I got a book signed to my daughter this year, because I believe she will need it when she grows up. She is 18 months old, now. It is also an Asian American novel.

15. I ask you whether this focus on the next generation is an Asian/Asian American thing, and/or an immigrant thing. You say: “I think that hope is what keeps the current generation going—if you don’t think things are going to get better, then my God, what else can you do? You have to hope that it will get better for our children and children’s children. It’s certainly an immigrant belief, an American Dream belief, and just belief in general as a human being.”

Your debut novel, The Reeducation of Cherry Truong: I think people should read it. I think people should give it to their children.

Pingback: Weekend Fiction: Excerpt from Aimee Phan's THE REEDUCATION OF CHERRY TRUONG — The Good Men Project