Dispatches: Being Asian American & Being an Asian in America

On first glance I know it seems that the title of my latest post is redundant—that being Asian American and being an Asian in America are one and the same.

But are they?

What does it mean to be “Asian American” and what does it mean to be an “Asian” in “America”?

The Asian American Studies Faculty at the University of California at Santa Barbara (UCSB–my alma mater).

Back in the 19th century, when the first significant wave of Asian immigrants (Chinese laborers, mostly Hakka people from southern China) came to the United States, Asians in America were understood to be foreign workers, a temporary solution to various labor shortages in the U.S.

I don’t want to wax pedantic and turn this into Asian American History 101, but I start with Chinese workers in the 19th C. because in many ways Asian Americans still live with that legacy of being seen as foreign, as outsiders, as non-citizens, as people who are not legitimately American. They/we/I are perpetually seen as Asians who happen to be living in America rather than as Asian Americans–people who belong here, who may have long and deep roots in the U.S.. Being Asian American doesn’t necessarily mean being a U.S. citizen. Claiming America and identifying as Asian American is as much about deciding that you believe in American cultural norms and values, regardless of whether you’re naturalized or whether you were born on U.S. soil, or whether you’re a recent immigrant.

Identifying as Asian American–deciding that you are Asian American–is a political act. It means that you recognize that there is such a thing as racial categories, for better or worse. It means that you understand that there is a long and complicated and violent history of racialization and racist state practices leveled against Asians in America from the 19th century (Chinese Exclusion Act, Paige Law, Gentleman’s Agreement, Japanese American Internment) to our present day (racial targeting of Muslim and Arab Americans following September 11). And it embraces diversity–because Asian American as a racial category encompasses a multiplicity of Asian ethnicities and nationalities. Asian American families come in a variety of forms, including multiracial, which we can see in the extended first family.

The number of folk who actively use the label “Asian American” as a self-descriptor is, according to the controversial Pew report that just came out, 19% (please go to this link for a full description for why the Pew Report is so problematic). But regardless of whether you identify as Chinese or Chinese American or Asian American, what unites people of Asian descent in the United States is that we are all still subject to being perceived as Asians in America: as being foreign, other, not-real-Americans. To put it another way: What Asian Americans and Asians in America all have in common, regardless of how we identify or where we come from, is that we are not white. And because we are not white, we are always going to be hyphenated Americans; we are always going to be perceived as not fully American.

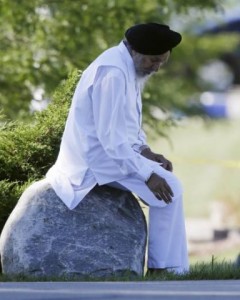

Not being white and not being seen as fully American or as foreign was probably a large reason why the Oak Creek Gurdwara in Wisconsin was targeted by white supremacist Wade Page. As all readers should no doubt already know, on the morning of Sunday, August 5, Page walked into the Sikh temple and enacted a violent rampage, killing six, wounding many more, terrorizing the community of Sikhs in Wisconsin and around the nation. In the days and weeks following Page’s act of violence, there has been much speculation about his motives, which some believe cannot be completely determined because he shot himself in the head (ostensibly he preferred suicide to being captured alive and interrogated and incarcerated). As this New York Times article describes, Page was being tracked by the Southern Poverty Law Center for his involvement with various white supremacist groups.

There are some who believe that Page confused Sikhism for Islam–that he had intended to kill Muslims instead of Sikhs. There are some who want to educate the public about Sikhs in hopes that this will prevent the Sikh community from being targeted by white supremacists with an agenda of Islamophobia. But as Amardeep Singh astutely notes,

“I also don’t think we should fool ourselves that all hostility will be resolved purely by education, nor should we presume that this shooter suffered only from ignorance. As a white supremacist, it seems safe to suppose, what mattered to the shooter was that he hated difference — and saw, in the Sikh gurdwara at Oak Creek, a target for that hatred.”

I’m going to take this one-step further. Whether Page was confused or not simply doesn’t matter. He was a known white supremacist. He did not like non-white people. He targeted the Sikh temple because he saw the people in the temple as being foreigners, as being other, as being non-America. They were Asians in America. They did not fit into Page’s conception of who is American. And no amount of education about Sikhism, as well intentioned as that may be, will prevent other Pages and other white supremacists from targeting non-white people. They will not see us as Asian American; they will see us as not belonging.

Also, it should go without saying that had Page opened fire in a mosque, his crime would be just as horrific. I think regardless of what your religious beliefs are or your racial or ethnic identification, we should all be able to agree that going into a place of worship and opening fire on people is always wrong and never justified.

There are many reasons to celebrate being Asian American, and so I don’t want to simply end by saying that Asian Americans should be afraid of being victims of hate crimes or should assimilate into American culture. On the contrary, the purpose of this post is to remind us that there is a richness and a diversity to being Asian American–that our experiences are very different from one another depending on our ethnic group, how long our families have resided in the U.S., our age, gender, sexual orientation, class, regional and religious affiliations. But despite our differences what unites us is that we are both Asian Americans and Asians in America, and we can learn from the past and hopefully work together, as allies, because what happened to the Sikhs in Wisconsin could happen (and has happened) to other Asian Americans–to Vincent Chin, to Japanese incarcerated during World War II, to Vietnamese refugees in the 1970s. We are all Sikh. We are all Asian American. We are all in this together.